When the world put Nazi leaders on trial after World War II, someone had to sit across from them, ask questions, and try to understand what made them tick. That person was Gustave Gilbert, an American psychologist who found himself face‑to‑face with some of history’s darkest minds.

Born in 1911 in New York City, Gilbert became famous not for lab experiments or therapy theories, but for his role at the Nuremberg Trials, where he served as the prison psychologist for high‑ranking Nazi officials.

There, he didn’t just observe them. More importantly, he listened, analyzed, and documented their thoughts in one of the most haunting psychological records of the 20th century.

Why Is Gustave Gilbert Famous?

Gustave Gilbert is best known for his work as the prison psychologist at the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials (1945–1946).

Fluent in German, he was tasked with monitoring the mental state of Nazi leaders awaiting trial. This means he was directly interacting with men like Hermann Göring, Rudolf Hess, and Joachim von Ribbentrop.

But Gilbert’s role went far beyond routine evaluations. He spent hours talking with the prisoners, recording their reflections, rationalizations, and emotional states. His goal was to understand the psychology of evil and how ordinary people could commit extraordinary atrocities.

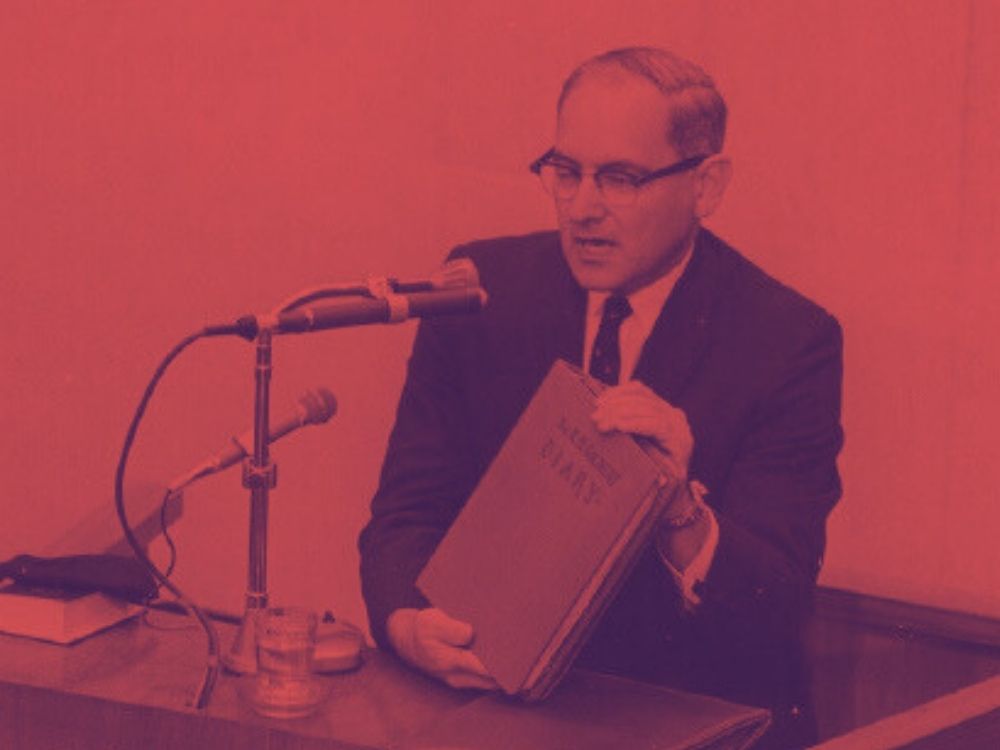

Those conversations became the basis for his book Nuremberg Diary (1947), a chilling yet also deeply human account of what happens when ideology and obedience override morality.

Gilbert’s work offered a rare psychological window into the minds of perpetrators, showing that evil isn’t always monstrous on the surface.

In fact, sometimes, it’s disturbingly ordinary.

What Did Gilbert Actually Discover?

Unlike many of the famous psychologists that we cover on this site, Gilbert wasn’t running experiments or testing theories. Instead, he was documenting the psychology of power, guilt, and denial in real time.

What he found was both fascinating and terrifying.

The Banality of Evil (Before It Had a Name)

Years before philosopher Hannah Arendt coined the phrase “the banality of evil,” Gilbert was already describing it.

He noted that many of the Nazi defendants weren’t psychotic or sadistic in the clinical sense. These were bureaucrats, soldiers, and politicians who had learned to suppress empathy in favor of ideology.

He concluded that evil often arises not from madness, but from moral blindness, the ability to rationalize cruelty as duty.

The Psychology of Obedience and Authority

Gilbert’s interviews revealed how obedience to authority can override individual conscience.

Many defendants claimed they were “just following orders,” a defense that would later inspire research by psychologists like Stanley Milgram, who tested how far people would go under authority pressure with his (in)famous Obedience Experiment.

Gilbert’s observations at Nuremberg were, in a sense, the real‑world prelude to those later experiments.

The Role of Conscience and Empathy

Gilbert believed that conscience (that is, our capacity for empathy and moral reasoning) is the true barrier against evil. He saw how easily that barrier could crumble when people surrender moral responsibility to institutions or leaders.

In his notes, he described Göring as charismatic but manipulative, Hess as paranoid and detached from reality, and others as emotionally numb or self‑justifying.

Through it all, Gilbert tried to answer one haunting question: How could they do it?

A Meeting of Minds: Gilbert and Frankl

While Gilbert was studying the perpetrators of the Holocaust, another psychologist, Viktor Frankl, was surviving it.

Frankl, an Austrian psychiatrist and concentration camp survivor, later wrote about finding meaning amid suffering in his book Man’s Search for Meaning.

Gilbert and Frankl never worked together, but their perspectives form two sides of the same psychological coin: Gilbert explored the psychology of cruelty, while Frankl explored the psychology of resilience.

Both sought to understand how human beings respond to extreme moral and existential crises: one from the side of the oppressed, the other from the side of the oppressors.

You can read more about Frankl’s story in our article, “Meet Viktor Frankl: Finding Meaning When Life Gets Messy.”

So What? Why Should You Care?

Gustave Gilbert’s work still echoes through psychology, ethics, and even modern discussions about war crimes and human behavior.

- His insights helped shape our understanding of moral reasoning, authority, and responsibility.

- His detailed records remain a crucial resource for historians and psychologists studying the roots of collective violence.

- And his legacy reminds us that understanding evil isn’t about excusing it, but about preventing it.

In a world that’s still grappling with authoritarianism, propaganda, and moral disengagement, Gilbert’s work feels as urgent as ever.

He showed that the line between good and evil doesn’t run between nations or ideologies.

Instead, it runs through every human heart.

Fast Facts and Fun Stuff

- Standout Achievement: Served as prison psychologist at the Nuremberg Trials and authored Nuremberg Diary, a psychological record of Nazi war criminals.

- Legacy: Pioneer in the psychology of evil, moral responsibility, and obedience to authority.

- Fun Fact: Before becoming a psychologist, Gilbert earned degrees in both psychology and sociology, a combination that helped him interpret behavior in both individual and cultural contexts.

- Pop Culture: While not a household name, Gilbert’s work influenced later depictions of psychological inquiry into evil, from documentaries to films about Nuremberg and the Holocaust.

Gilbert in a Nutshell

Gustave Gilbert wasn’t studying the mind in a lab. Instead, he was studying it in history’s darkest courtroom.

By documenting how ordinary people justify extraordinary crimes, he forced psychology to confront one of its most uncomfortable truths: understanding evil means recognizing our own capacity for it.

Gilbert’s work challenges us to think about morality not as an abstract ideal, but as a daily choice.

Perhaps most chillingly of all, however, he showed that the worst atrocities don’t always come from madness. The terrifying truth is that they often come from people who stop questioning, stop feeling, and stop seeing others as human.

So, as we wrap up with today’s Tomato Takeaway, now I’d like to hear from you.

Do you think evil is something innate, or is it something that emerges when empathy and conscience are switched off?

Share your thoughts in the comments and join the discussion below.

Fueled by coffee and curiosity, Jeff is a veteran blogger with an MBA and a lifelong passion for psychology. Currently finishing an MS in Industrial-Organizational Psychology (and eyeing that PhD), he’s on a mission to make science-backed psychology fun, clear, and accessible for everyone. When he’s not busting myths or brewing up new articles, you’ll probably find him at the D&D table or hunting for his next great cup of coffee.