Ever tried ordering coffee abroad and realized your idea of “normal” isn’t universal? In Italy, ordering a cappuccino after noon gets you side‑eye so sharp it could cut glass. In Japan, slurping noodles loudly is polite, like applause for the chef. In the U.S., people microwave fish in office kitchens like it’s no big deal (spoiler: it is a big deal, Steve).

Welcome to the world of culture messing with your psychology.

That’s the heart of Cultural and Cross‑Cultural Psychology: the study of how culture shapes our minds, and how comparing across cultures reveals both differences and universals.

If your brain is a computer, culture is the operating system, and not everyone is running the same version of Windows. Some are on macOS, some are running Linux, and some are still rocking that one family computer that screams like a banshee every time it tries to connect to the internet.

The Problem It Tried to Solve

For most of psychology’s history, researchers assumed human behavior was basically universal. They ran experiments on college students in the U.S. or Europe and generalized the results to “all humans.”

Spoiler: those students were overwhelmingly WEIRD, which is to say Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic.

Not exactly a fair sample of humanity, eh? It’s like taste-testing a new soda flavor on five frat houses in Ohio and then declaring it’s “the world’s favorite drink.”

This WEIRD bias meant that psychology’s “universal truths” were often just reflections of Western culture. For example, early studies on moral reasoning concluded that children progress through stages that emphasize individual rights and abstract principles.

But when researchers studied kids in other cultures, they found moral reasoning often emphasized community, duty, or spiritual harmony instead. The “universal” stages weren’t so universal after all.

Turns out “be yourself” isn’t the only moral compass, and that sometimes it’s more like “don’t you dare embarrass grandma.”

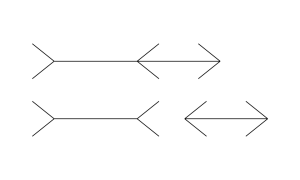

Even basic perception turned out to be culture‑shaped. The Müller‑Lyer illusion (those two lines with little arrowheads that make one look longer) reliably tricks Westerners.

But people from non‑industrialized societies, who don’t grow up surrounded by right angles and carpentered corners, often aren’t fooled. It wasn’t that their eyes were different; their environments trained their brains differently.

So the problem was clear: psychology couldn’t keep pretending that a sample of American undergrads represented the whole human species. Cultural and cross‑cultural psychology emerged to ask: Which parts of our psychology are truly universal, and which are cultural fingerprints?

Roots of Cultural & Cross‑Cultural Psychology

The story begins with anthropology and psychology bumping into each other at the academic dance.

Anthropologists like Margaret Mead and Ruth Benedict showed that adolescence, gender roles, and family structures vary wildly across cultures. Their work challenged the idea that human development followed a single, fixed path. Mead basically said, “Teen angst is not a biological law. It’s just how Americans do puberty.”

Meanwhile, psychologists like Lev Vygotsky in the early 20th century argued that children’s development is inseparable from cultural tools like language, symbols, and social practices. He saw culture not as window dressing but as scaffolding for the mind itself. No culture means no mind, kind of like trying to build IKEA furniture without the little Allen wrench.

By the mid‑20th century, researchers like John Berry and Harry Triandis started systematically comparing cultures. Berry studied how people adapt when they move between cultures, developing models of acculturation. Triandis dove deep into individualism and collectivism, laying the groundwork for one of the most famous cultural dimensions.

Around the same time, Dutch social psychologist Geert Hofstede analyzed data from IBM employees across the globe and mapped out cultural dimensions like power distance and uncertainty avoidance. Apparently, selling typewriters also gave him a front-row seat to human diversity. Who would have thought?

And so, in the 1980s and 90s, cultural psychology emerged as a distinct voice. Scholars like Richard Shweder, Hazel Markus, and Shinobu Kitayama argued that culture and psyche don’t just influence each other, but rather they co‑create each other.

This means that the mind isn’t a universal computer that culture decorates; it’s built in partnership with culture from the ground up.

Together, these streams created a field that gave psychology a passport and said, “Stop pretending the world is one giant college campus in Ohio.”

Core Ideas of Cultural & Cross‑Cultural Psychology

Here’s the greatest hits playlist of concepts that make this field both so juicy and so relevant.

But before we go diving into the specifics, it helps to remember what this field is trying to do.

Cultural psychology isn’t just a list of quirky customs, like “Germans love punctuality” or “Brazilians throw better parties.” It’s about uncovering the deep wiring underneath to see the ways culture shapes how we think, feel, and even notice the world around us.

Cross‑cultural psychology takes that wiring and asks: how does it compare across different groups? Together, they’re like scientists running A/B tests on humanity, except instead of testing website buttons, they’re testing entire worldviews.

What emerges are some core themes and big ideas that show just how much culture sneaks into our psychology.

Individualism vs. Collectivism

This is the Beyoncé single of cultural psychology. Wherever you go, everyone knows it.

In individualist cultures like the U.S., people are encouraged to stand out, pursue personal goals, and say “you do you.”

However, in collectivist cultures like Japan or China, people are more encouraged to fit in, maintain harmony, and say “we’re all in this together.”

This difference shows up everywhere: in how students explain success (“I worked hard” vs. “my teachers supported me”), in how conflicts get resolved (direct confrontation vs. polite avoidance), and even in advertising slogans. American ads say, “Because you’re worth it.” Japanese ads say “Bringing harmony to your family.”

Same shampoo, different worldview.

Self‑Construals

Related to individualism and collectivism is the idea of self‑construals. In independent cultures, the self is seen as unique, defined by personal traits: “I’m creative, ambitious, funny.” In interdependent cultures, the self is defined by relationships: “I’m a daughter, a friend, a colleague.”

This shapes not just how people describe themselves, but how they think.

Independent selves focus on personal achievement and self‑expression. Interdependent selves focus on fitting in and fulfilling obligations.

Neither is better. They’re just different cultural blueprints for being human.

Cultural Dimensions

Remember our friend Hofstede from earlier in this article? Well, this is where he comes in!

Hofstede’s framework gave researchers a way to map cultural differences beyond the standard East vs. West.

Power distance measures how much people accept hierarchy. Uncertainty avoidance measures how comfortable people are with ambiguity. Masculinity vs. femininity measures whether a culture values competition or care.

Now, naturally, these dimensions aren’t perfect. After all, cultures are WAY too complex to be reduced to a few numbers! However, Hofstede’s framework gave psychology a language for talking about cultural variation without collapsing into stereotypes.

You can think of them as rough sketches, not Instagram-ready portraits.

While you’ll certainly encounter Hofstede’s framework in psychology and sociology classes, it’s also the go-to framework in business schools when learning about how business is conducted internationally.

Cognition & Perception

Culture shapes not only what we think, but also how we think.

Generally speaking, Westerners tend to use analytic thinking, focusing on objects and categories. Meanwhile, East Asians often use more holistic thinking, focusing on context and relationships.

So, for example, you can show an American a picture of a fish tank, and they’ll describe the biggest fish. But if you show a Japanese participant, they’ll likely describe the whole scene: the plants, the water, the relationships between fish.

Same tank, different story.

As we covered earlier in this article, optical illusions vary by culture. People raised in “carpentered” environments with lots of straight lines and right angles are more likely to be fooled by certain illusions (like the Müller‑Lyer illusion we showed) than people raised in natural environments.

Our senses aren’t hardwired; they’re culturally tuned!

Emotion & Expression

Emotions may be universal, but how we express them is a deeply cultural performance

Americans smile at strangers, whereas Finns tend to save smiles for people they actually like because smiling at strangers can seem suspicious. Like, what are you plotting? Similarly, in Japan, showing anger in public can make you look immature, but in the U.S., it can make you look assertive or even powerful.

Cultures have what psychologists call “display rules” that are kind of like unwritten scripts that dictate when it’s okay to cry, laugh, or shout.

It’s important to learn these rules, as breaking them can get you labeled as rude or weird. Depending on the situation and where you’re at, it could even be hard to tell which of those outcomes is worse!

Even physical signs of emotions can shift. Studies show that Americans tend to focus on the mouth when reading facial expressions, while Japanese participants focus more on the eyes. As such, even emojis look different across cultures!

Consider the classic smiley face, which in the West is 🙂 (with the mouth doing the work) while in Japan it’s ^_^ (with the eyes doing the work).

Language & Thought

The Sapir‑Whorf hypothesis suggests that language shapes thought.

For example, in some Aboriginal Australian languages, people don’t use “left” and “right” but cardinal directions (i.e., north, south, east, west) even in small talk. That means they always know where they are, like human GPS systems. (As someone who is notoriously horrible at directions, I’m so envious!)

Bilinguals often report feeling like slightly different people depending on the language they’re speaking, because each language carries its own cultural baggage.

To use my own experience as an example here, in English, I tend to feel energetic and whimsically humorous with a default setting of “late-night talk show host audition”. But in French, I feel more passionate and low-key like a café philosopher ordering another latte while pondering the nuances of pondering nuances about pondering nuances.

But then, when I try to practice my (very basic) Russian at my favorite restaurant, I mostly feel full because babushka keeps shoving more and more food in front of me. Apparently, in Russian, “love” is spelled “b-o-r-s-c-h-t”.

Language describes our reality, but more importantly, it nudges us into different ways of experiencing it.

Acculturation

What happens when cultures meet? John Berry’s model describes four strategies: assimilation (adopting the new culture), integration (blending both), separation (sticking to the old), and marginalization (disconnected from both).

These patterns show up in immigrant communities, in second‑generation kids navigating two worlds, and in anyone juggling multiple cultural identities.

For example, you might picture a teenager in Los Angeles who listens to K-Pop, eats tacos, and texts in Spanglish. That’s integration in action.

On the other hand, you might consider someone who moves to Paris and insists on only eating at American fast-food chains. That’s separation (with extra fries!).

The thing about acculturation is that it’s not just academic, but, most importantly, it’s lived. It shapes identity, belonging, and sometimes even mental health.

Integration often predicts the best outcomes, but the path isn’t always smooth. Culture clash can feel like trying to run two apps on a phone that keeps freezing up. Without the right support, it can get exhausting even if it is technically possible.

Why This Perspective Was Revolutionary

Cultural and cross‑cultural psychology shook psychology out of its WEIRD bubble. For decades, the “average human” in research was basically a college sophomore in sneakers. This field said: “Cool, but what about the other… you know… 7 billion people?”

It revealed that many so‑called “universal” findings were actually culture‑bound.

Take self‑esteem. Western research treated it as absolutely essential for well‑being. But in East Asian cultures where humility and self‑criticism are valued, people can thrive without high self‑esteem in the traditionally Western sense.

The revolution wasn’t just in pointing out differences, but in reframing psychology itself: the mind isn’t just biological, it’s bio‑cultural.

This perspective also expanded psychology’s mission. It wasn’t enough to study neurons and behavior in a vacuum; you had to study the cultural worlds people inhabit. That meant psychology had to become more global, more inclusive, and more humble.

And once you see that, it’s hard to go back to pretending one culture’s psychology is everyone’s psychology.

Critiques and Limitations

For all of the good of cultural and cross-cultural psychology, the truth still stands that studying culture is just going to be messy any way you slice it, and critics are quick to point out the pitfalls.

The immediate problem at play is stereotyping.

It’s tempting to say “all Asians are collectivist” or “all Americans are individualist,” but real people simply don’t fit neatly into boxes. Cultures are wonderfully diverse within themselves, and individuals often mix values from multiple traditions.

Similarly, the risk of oversimplification is another challenge.

Frameworks like Hofstede’s dimensions are useful, but they also risk flattening complex cultural realities into tidy little scales. Real life is more like jazz than a metronome. It’s fluid, improvised, and full of exceptions.

And that’s why methodology is another key sticking point. Translating surveys across languages is tricky, and researchers have to make sure that concepts mean the same thing in different contexts.

So, for example, “Happiness” in English might not map perfectly onto “幸福” (xìngfú) in Chinese, which emphasizes long‑term harmony rather than momentary joy.

Finally, there’s the tension between universals and specifics. Psychologists want to find patterns that apply to all humans, but they also want to respect cultural uniqueness. Balancing those goals is a lot like walking a tightrope: lean too far one way, and you miss the bigger picture; lean too far the other, and you erase important differences.

Legacy and Modern Influence

Despite the challenges, cultural and cross‑cultural psychology have reshaped the field in a massively important way.

Today, no serious psychologist can ignore culture.

The insights of this field ripple into business, education, healthcare, and diplomacy. Global companies train employees in cultural intelligence so they don’t accidentally offend clients. Teachers adapt lessons for multicultural classrooms. Doctors and therapists consider cultural beliefs about illness, healing, and mental health.

It’s also deeply relevant in everyday life. Anyone who’s traveled abroad knows the jolt of culture shock, that moment you realize your “normal” is someone else’s “strange.”

But even within a single country, cultural psychology helps explain misunderstandings across regions, generations, or communities. It gives us tools to build empathy, adapt to diversity, and navigate an increasingly interconnected world.

Cultural and cross‑cultural psychology turned psychology into a truly global science. Instead of assuming one cultural lens fits all, it did the important work of inviting the field to embrace the many ways of being human.

Tomato Takeaway

Cultural and cross‑cultural psychology remind us that our minds aren’t just shaped by neurons and hormones. They’re also shaped by traditions, languages, and the social worlds we inhabit. Culture is baked into how we think, feel, and relate to others.

So, as we wrap up this look at cultural and cross-cultural psychology, here’s today’s Tomato Takeaway for you…

Think back to a time you experienced culture shock. Maybe it was a food, a custom, or a gesture that surprised you. What did it teach you about how your own culture has wired your brain?

Share it in the comments, and let’s swap stories from our global minds.

Fueled by coffee and curiosity, Jeff is a veteran blogger with an MBA and a lifelong passion for psychology. Currently finishing an MS in Industrial-Organizational Psychology (and eyeing that PhD), he’s on a mission to make science-backed psychology fun, clear, and accessible for everyone. When he’s not busting myths or brewing up new articles, you’ll probably find him at the D&D table or hunting for his next great cup of coffee.