Your brain is not a chill roommate. It doesn’t just sit back, quietly cataloging the world like a filing clerk.

No, your brain is more like that one friend who insists on organizing the group photo before anyone even asks. It’s constantly grouping, sorting, filling in gaps, and insisting it sees patterns, sometimes even when they aren’t even there.

That’s why you can look at a bunch of dots and suddenly see a constellation, or glance at a half‑finished logo and instantly know what it’s supposed to be. It’s why you can recognize “Happy Birthday” whether it’s sung by Beyoncé or your tone‑deaf uncle. Your brain doesn’t just process parts; it insists on the whole picture.

This very human tendency gave rise to one of psychology’s most fascinating schools of thought: Gestalt psychology, the movement that declared, “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.”

The Problem Gestalt Tried to Solve

At the turn of the 20th century, psychology was kind of like a messy group project where no one quite agreed on the assignment.

First, you’ve got the Structuralists who were busy dissecting mental life into microscopic pieces, convinced that if they cataloged every little “atom” of sensation, the big picture would magically appear.

Meanwhile, the Behaviorists were rolling their eyes and saying, “Forget the mind, it doesn’t even exist! All we need is stimulus and response. Rats press levers, humans press buttons, end of story.”

But the everyday experience of being human didn’t fit neatly into either camp.

People weren’t walking around perceiving the world as a jumble of disconnected dots and dashes. They were hearing melodies that stayed recognizable even when played in a different key. They were seeing faces, not just eyeballs and noses floating in space like a Mr. Potato Head gone rogue.

That’s when Max Wertheimer, Kurt Koffka, and Wolfgang Köhler looked at this psychological tug‑of‑war and essentially said, “Guys, you’re missing the point. The mind doesn’t just record reality like a camera. It organizes, interprets, and sometimes even invents meaning out of thin air.”

Gestalt psychology was their way of flipping the table and saying: to understand the mind, you have to look at the whole picture… literally!

The Founders and the Famous Phrase

The story of Gestalt psychology really took off in 1912 when Max Wertheimer was on a train (because apparently all great psychology ideas happen on trains).

He noticed the phi phenomenon, which is the illusion of motion created when lights flash in rapid succession. Think of those old marquee signs where bulbs light up in sequence to make an arrow “move.” Nothing is actually moving, but your brain insists it is.

Movies work the same way: a bunch of still frames projected quickly enough convinces your brain you’re watching Iron Man fly, not Robert Downey Jr. standing in front of a green screen. One of those is WAY more interesting!

So you see, Wertheimer realized that this wasn’t just a neat party trick. It actually revealed something quite profound: our brains are natural storytellers, stitching fragments into wholes.

Together with Koffka and Köhler, Wertheimer turned this insight into a rallying cry: “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” Which, let’s be honest, is a much cooler slogan than “Stimulus plus response equals behavior.”

Gestalt Principles of Perception

So how exactly does your brain turn chaos into order? Gestalt psychologists identified principles that show how we naturally group, sort, and smooth the messy world into something that makes sense.

Take proximity. Put some dots close together and suddenly they’re not dots, they’re a constellation, a flock of birds, or at the very least, a connect‑the‑dots puzzle begging to be solved.

Or take similarity. Humans love matching outfits, whether it’s sports uniforms, traffic cones, or M&M colors. If things look alike, our brains immediately assume they belong together.

Then there’s closure, which proves that our brains hate unfinished business more than Netflix cliffhangers. Show us a circle with a gap, and we’ll mentally seal it shut. That’s why logos like the WWF panda look complete even though parts are missing. Your brain can’t resist playing “finish the picture”!

Continuity is another sneaky one. Instead of seeing lines crossing as a mess of fragments, we see smooth paths that keep flowing. This is why we can read cursive handwriting without crying (most of the time) and why subway maps don’t look like spaghetti.

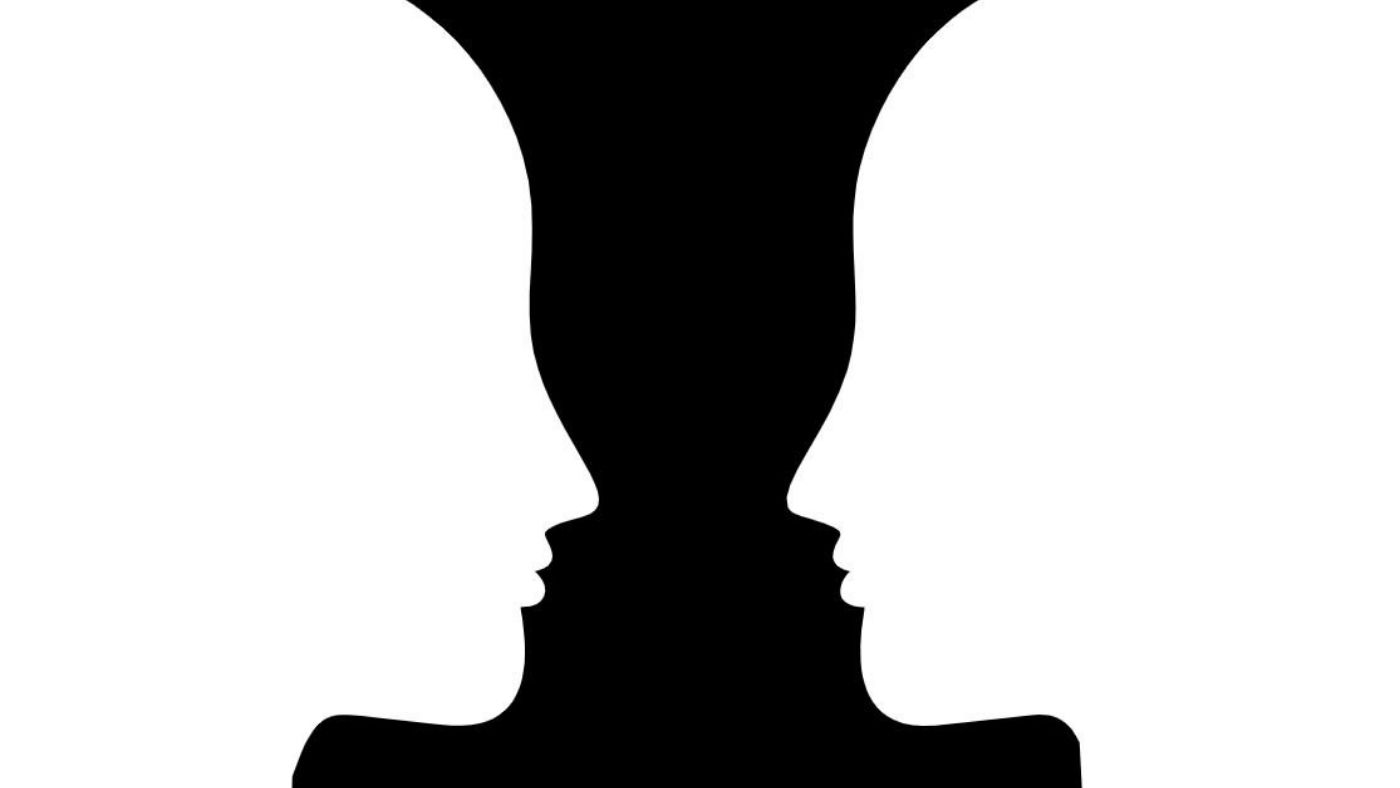

And finally, we’ve got figure‑ground. This is the magic trick that lets you read black letters on a white page, or flip between seeing a vase and two faces in Rubin’s illusion (this article’s cover image). Without figure‑ground separation, the world would look like your camera roll after your cat walked across the keyboard: a jumbled mess.

These aren’t just optical parlor tricks. They’re the brain’s operating system. They explain why memes make sense, why logos stick in your mind, and why you can never unsee the hidden arrow in the FedEx logo once someone points it out.

Köhler’s Chimps and Insight Learning

Though Gestalt wasn’t only about how we see, it was also about how we think.

While Behaviorists were busy timing how long it took rats to run mazes, Wolfgang Köhler was hanging out with chimpanzees in Tenerife. It was there that he noticed something fascinating.

When a banana was placed just out of reach, the chimps didn’t flail around in trial‑and‑error chaos like Behaviorism predicted. They didn’t think, “Press lever, get pellet.” Instead, they paused, scratched their heads, and then, boom, stacked boxes or grabbed sticks to snag the banana. Problem solved.

Köhler called this insight learning: that sudden “aha!” moment when the puzzle pieces just “magically” click into place. It was psychology’s version of a lightbulb turning on, except instead of Edison, it was a chimp with a stick.

This challenged the Behaviorist idea that learning was always slow, incremental conditioning. Gestalt showed that sometimes, the mind can reframe a problem, reorganize the pieces, and leap straight to a solution in one creative jump.

It’s the same feeling you get when you finally solve a crossword clue or realize you’ve been singing the wrong lyrics to a song for the past ten years.

Why Gestalt Was Unique

What made Gestalt stand out was its refusal to treat humans like passive sponges or glorified lab rats.

Where Structuralism saw a mosaic of tiny sensations, Gestalt saw the full mural that emerges when the tiles fit together. Where Behaviorism saw a simple chain of stimulus and response, Gestalt saw the interpretation that gave those responses meaning.

This was radical. It meant psychology had to grapple with context, perspective, and organization, not just raw data.

A melody isn’t just a series of notes; it’s the pattern that ties them together. A joke isn’t just words; it’s the timing, the delivery, the pause before the punchline that makes it funny. A face isn’t just a collection of features; it’s the arrangement that makes you recognize your best friend instead of mistaking them for a confused and possibly terrified stranger.

Gestalt also crossed disciplinary borders like an over‑eager exchange student.

Artists had long known that composition mattered more than individual brushstrokes. Designers were already using proximity and closure to make posters pop. Teachers instinctively knew that students learned better when they saw the big picture instead of memorizing disconnected facts.

Gestalt psychology gave all of these intuitions a scientific backbone.

Gestalt was unique because it treated humans not as machines reacting to the world, but as active creators of meaning. And let’s be honest, that’s a much more flattering view of ourselves than “stimulus‑response robot.”

The Legacy of Gestalt Psychology

Although Gestalt psychology as a formal school faded by the mid‑20th century, its fingerprints are still everywhere to this day.

The cognitive revolution of the 1950s and 60s borrowed heavily from Gestalt’s central insight that the mind actively organizes information rather than passively receiving it. Every time a cognitive psychologist talks about schemas, problem‑solving, or memory organization, there’s a little whisper of Gestalt in the background saying, “Told you so.”

Neuroscience has also circled back to Gestalt ideas.

Brain imaging shows that neural networks don’t just record sensory input, but they also integrate it into coherent wholes. Your brain is constantly filling in the blanks, smoothing over gaps, and making sense of chaos. Basically, Gestalt was describing the brain’s operating system before MRI machines even existed.

And outside academia? Gestalt principles are the unsung heroes of modern life!

Graphic designers use them to craft logos that stick in your head like catchy jingles. UX designers rely on them to make websites feel intuitive instead of overwhelming. Advertisers exploit them to make products feel familiar and cohesive. Heck, even your smartphone’s home screen is designed with Gestalt rules to guide your eyes without you realizing it.

Culturally, we still live in Gestalt’s shadow. We celebrate “aha!” moments, we praise designs that “just work,” and we instinctively understand that the big picture matters more than the isolated details.

Gestalt may not be a household word, but its DNA runs deep through psychology, art, design, and the way you navigate your daily life, from solving puzzles to scrolling Instagram.

Tomato Takeaway

Gestalt psychology was a game‑changer because it reminded us that the mind isn’t a filing cabinet for random sensations or a machine that spits out reflexes. It’s a meaning‑making powerhouse!

The whole really is greater than the sum of its parts. That’s why you hear a melody instead of just notes, see a face instead of just features, and laugh at a meme instead of just some random pixels.

But we’ll wrap up here with this Tomato Takeaway: next time you’re staring at an optical illusion, admiring a clever logo, or having one of those glorious “aha!” moments, tip your hat to the Gestalt psychologists. They were the ones who figured out that your brain is less like a camera and more like a director who is constantly editing, cutting, and stitching reality into a story that makes sense!

Now it’s your turn to join the conversation.

What’s your favorite Gestalt moment? The FedEx arrow you can’t unsee, the vase‑faces illusion, or that time you solved a problem by suddenly looking at it differently?

Drop it in the comments and let’s see which Gestalt mind‑games blow your mind the most!

Fueled by coffee and curiosity, Jeff is a veteran blogger with an MBA and a lifelong passion for psychology. Currently finishing an MS in Industrial-Organizational Psychology (and eyeing that PhD), he’s on a mission to make science-backed psychology fun, clear, and accessible for everyone. When he’s not busting myths or brewing up new articles, you’ll probably find him at the D&D table or hunting for his next great cup of coffee.