Do you remember the Monopoly Man having a monocle? Or the Berenstain Bears being spelled “Berenstein”? Or Darth Vader saying the famous line, “Luke, I am your father”?

If so, congratulations: your memory has betrayed you. None of those are correct. And yet, millions of people “remember” those exact same details with absolute confidence.

That strange, collective misremembering has a name: The Mandela Effect. It’s a phenomenon where groups of people share the same false memory, sometimes so vividly that it feels like proof of alternate realities.

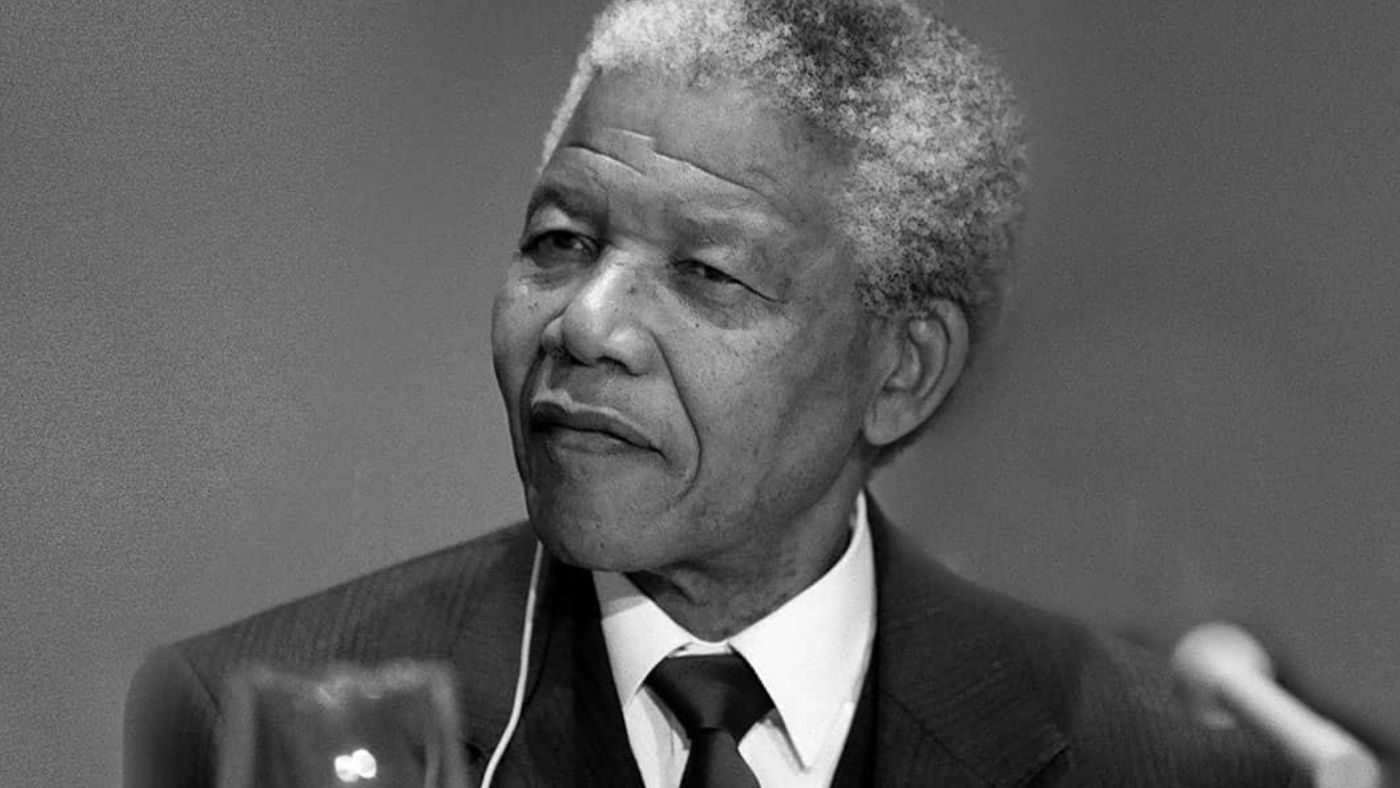

The term itself was coined in 2010 by paranormal researcher Fiona Broome, who discovered that she, along with countless others, clearly remembered Nelson Mandela dying in prison in the 1980s. In reality, Mandela was released in 1990, became president of South Africa in 1994, and lived until 2013. But for those who swore they remembered his funeral decades earlier, the discrepancy felt eerie, even unsettling.

The Mandela Effect has since exploded into internet culture, becoming both a pop-psychology curiosity and a cultural obsession. But behind the memes and Reddit threads lies something deeper: a fascinating window into how memory works, how culture shapes our perceptions, and how fragile our sense of “truth” really is.

So let’s dive in deeper, shall we?

Everyday Examples

The Mandela Effect has become a kind of cultural parlor game: spotting details that “everyone remembers wrong.”

Take the beloved children’s book series about a family of bears. Many people insist they grew up reading The Berenstein Bears, spelled with an “-ein.” But the actual spelling is The Berenstain Bears, with an “-ain.” The difference is tiny, but the false memory is widespread and passionately defended.

Or consider the Monopoly Man. In our collective imagination, he sports a top hat, a mustache, and, of course, a monocle. Except he never had one. The mental image is so strong that many people feel shocked, even betrayed, when shown the actual logo.

Other examples include Pikachu’s tail (no black tip, despite countless memories to the contrary), C-3PO’s mismatched silver leg in Star Wars, and the Fruit of the Loom logo (no cornucopia, even though many of us could swear we saw one).

What makes these examples so compelling isn’t just that people misremember. That’s not super shocking or impressive. What is so fascinating about the Mandela Effect is that so many people misremember in the same way. That shared error feels almost supernatural, as if we’ve all slipped into the wrong timeline.

The Science Behind It

Psychologists, however, see the Mandela Effect as less about alternate universes and more about the quirks of human memory.

Contrary to the way we often imagine it and would like to believe, memory isn’t like a video recording.

It’s actually reconstructive. Each time we recall something, our brains don’t “play back” a perfect copy; instead, they rebuild the memory from fragments, influenced by context, assumptions, and even suggestions.

That means that memory is flexible, creative, and prone to error.

Several psychological processes are at play:

- Schemas and mental shortcuts: Our brains rely on mental templates, or schemas, to make sense of the world. A monocle fits the Monopoly Man’s “wealthy gentleman” schema, so our memories insert it.

- Confabulation: We sometimes unconsciously fill in missing details with invented ones, later recalling them as real.

- Source confusion: We may mix up where a memory came from. For example, confusing a parody or cultural reference with the original.

- Social reinforcement: When others confidently share the same false memory, it strengthens our own conviction. If “everyone” remembers it, it must be true, right?

- The internet effect: Online forums, videos, and memes amplify these shared errors, making them feel even more widespread and validated.

From a scientific perspective, the Mandela Effect is less about glitches in the Matrix and more about the fascinating and fallible ways our brains construct reality.

Bugs Bunny at Disneyland

One of the most striking demonstrations of false memory comes from a study by psychologist Elizabeth Loftus and her colleagues in the early 2000s. Participants were shown a fake advertisement featuring Bugs Bunny at Disneyland.

Of course, Bugs Bunny is a Warner Bros. character. He has never been (and could never be) at a Disney park. Yet when later asked about their own theme park experiences, about a third of participants “remembered” meeting Bugs Bunny at Disneyland. Some even described vivid details like shaking his hand or hugging him.

The study illustrates just how malleable memory can be. A simple suggestion, placed in a believable context, can create entire recollections of events that never occurred. The Bugs Bunny experiment is essentially a laboratory version of the Mandela Effect: a false detail, reinforced socially, becomes a “memory” that feels as real as any other.

(Note: This is actually one of my favorite modern psychology experiments, so stay tuned as we’ll be giving it its own dedicated article in the near future!)

Why It Matters

At first glance, the Mandela Effect might seem like harmless trivia. At the end of the day, who really cares if you misremember a cartoon bear’s name or a movie quote, right?

But, as is often the case with these things, the implications go much deeper.

False memories can influence eyewitness testimony, leading to wrongful convictions. They can shape historical understanding, with entire groups misremembering key events. They can even affect personal identity in the sense that, if you’re confident about something in your past that never happened, what does that mean for your sense of self?

In the modern digital age, the Mandela Effect also highlights how misinformation spreads. A single error, once repeated and reinforced online, can quickly feel like fact. The same psychological processes that make us misremember logos also make us vulnerable to fake news.

Pop Culture and Internet Culture

The Mandela Effect has become a cultural phenomenon in its own right. Entire YouTube channels and TikTok accounts are devoted to cataloging examples. Reddit threads debate whether these false memories are evidence of parallel universes, glitches in the Matrix, or just collective brain farts.

Naturally, Hollywood has tapped into the same fascination. Movies like The Matrix, Inception, and Marvel’s multiverse films (Loki, Spider-Man: No Way Home) all play with the idea of fractured realities and divergent timelines.

The Mandela Effect fits perfectly into this cultural moment, where science fiction and internet folklore blur together with the real world.

A sizable part of the appeal is emotional. Discovering a Mandela Effect feels spooky. It’s the thrill of realizing that something you “knew” was wrong, and that countless others “knew” it too. It feels like peeking behind the curtain of reality, even if the real explanation is just our brains being… well… human.

Science vs. Multiverse

The Science Explanation:

Psychologists argue that the Mandela Effect is simply the result of how memory works. Our brains reconstruct, rather than replay, memories. In this process, they fill in gaps with assumptions that are influenced by cultural cues and social reinforcement.

In this view, the Mandela Effect is proof of memory’s fallibility, not of a fractured reality.

The Multiverse Theory:

Perhaps unsurprisingly, internet culture has embraced a more fantastical explanation: maybe these false memories are glimpses into alternate timelines or parallel universes. In this view, you really did see the Monopoly Man with a monocle, but just not in this timeline.

While there’s no scientific evidence for this, the theory thrives online because it’s fun, spooky, and taps into our love of sci-fi.

Using the Mandela Effect for Insight

Ok, so what do we do with all this?

Well… beyond the memes and debates, the Mandela Effect offers a valuable lesson about human psychology.

First and foremost, it reminds us to be humble about our own memories. Confidence doesn’t equal accuracy, and even vivid recollections can still be wrong (much like swearing that you saw and even hugged Bugs Bunny at Disneyland).

In that same light, it encourages us to fact-check, to seek outside perspectives, and, importantly, to recognize how easily misinformation can take root. It can start with small, trivial things, but continue to spread to much larger and more impactful things.

It also highlights the social side of knowledge. What we “know” is often shaped not by direct experience but by what others around us insist is true. The Mandela Effect is memory plus peer pressure, amplified a millionfold by the internet.

But I really hope your takeaway from this article isn’t doom, gloom, and despair. Luckily, there’s an optimistic angle to this conversation as well!

Just as false memories can spread, so can truth, curiosity, and critical thinking. By understanding phenomena like the Mandela Effect, we become better equipped to navigate a world where information is abundant (often overwhelmingly so) but not always reliable.

Wrap-Up

The Mandela Effect isn’t just an internet conspiracy rabbit hole or collection of quirky misremembered details. When we look under the surface of this phenomenon, we see that it’s a reminder of how memory works, how culture shapes our perceptions, and just how fragile our sense of truth can be.

So the next time you’re sure the Monopoly Man has a monocle, or that Mandela died in the 1980s, pause and smile. You’ve just experienced the strange, fallible, and collective magic of human memory.

Now it’s your turn to join the conversation!

What’s your favorite Mandela Effect? Have you ever been absolutely certain about something only to find out it never happened? Share your story in the comments and let’s chat about which “glitches in the Matrix” have fooled you.

Fueled by coffee and curiosity, Jeff is a veteran blogger with an MBA and a lifelong passion for psychology. Currently finishing an MS in Industrial-Organizational Psychology (and eyeing that PhD), he’s on a mission to make science-backed psychology fun, clear, and accessible for everyone. When he’s not busting myths or brewing up new articles, you’ll probably find him at the D&D table or hunting for his next great cup of coffee.